I've been itching to make some more boxes. I really liked the way my

pencil top boxes with ebony splines came out. With the exception of the lids. Those were hard to fit properly. They ended up being a little too sloppy for my liking. So, I decided to try a different style of lid.

I also wanted to use some of the thin hardwood boards that I bought for my laser, because, well, they didn't need planed to thickness and because I had a large collection of them that was getting a bit out of hand. However, the thin boards were not thick enough to cut a rabbet or a dado into, so the top and bottom would need another way to attach. I always wanted to try the kind of box that has a second layer of wood that lines the interior, so that's what I went for. Usually those kinds of boxes have the interior panels stick up above the rim and the lid fits down over the lip created by the interior wall. This is how you make boxes that start off closed on the top and bottom, then you cut through the side to separate the top from the rest of the box. These boxes would not be like that. Instead, the interior wall would be shorter than the exterior sides of the box, and allow the bottom of the lid to set down inside. You'll see what I mean.

Walnut is my favorite wood (one of), so that's what I wanted to make the sides from. Walnut boards for my laser cost about $2 each, and poplar boards cost less than $1 each, so I decided to make the interior walls, the lid bottom, and box bottom out of poplar.

I cut side pieces from walnut, about 2.5" tall and 4.5" long. I cut enough to make five boxes. I planned to use box joints for the outer walls, and then precisely fitted butt joints on the interior walls. Unfortunately, I ran into a little trouble with

my box joint jig. It didn't want to cooperate. And though I had made

box joint boxes with this jig before, today it was not happening. I ruined the ends of two (luckily only two) of the walnut boards before quitting in disgust and ordering an

INCRA I-Box jig on Amazon. But that was going to take a week to arrive, and I didn't want to wait that long, so the next day I went back into the workshop and tried something else.

I decided to miter the corners, like I did with the pencil top box. But because these boards were much thinner, I was going to need a more delicate method of mitering the edges than the table saw. I was going to need a hand plane shooting board with a 45 degree "donkey-ear" attachment.

Unfortunately, do to the aggravating previous day, I wasn't in much of a mood to take pictures during the creation of the shooting board or the "donkey-ear". And frankly, it came together very fast and there isn't much too it. Suffice to say, it turned out rather well and seems to work pretty good. Might need some tweaking to make it more square, but it was good enough. Now I could use a hand plane to put very precise 45 degree miters on the ends of all the walnut boards.

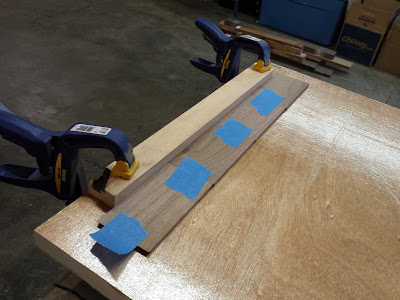

I lined up the boards end to end, outer faces facing up, and made sure they were square against a straight edge. Then I put masking tape at each of the joints. The masking tape will serve as a clamp to hold all the sides tightly in place as the glue dries.

Then I flipped the boards over, exposing the mitered edges, and applied glue.

Once the glue was applied, I folded up the sides and stuck another piece of tape on the last edge to hold it in a box shape. I made a quick jig out of some scrap wood to hold the box sides square while the glue dried. My jig could hold two boxes square at a time. They only needed to be in it until the glue started to set up.

Next, I cut pieces of poplar to serve as the bottom of the box and for the interior walls of the box. I dialed in the size of each piece using the shooting board. But this time, I didn't use the "donkey-ear". The interior pieces have 90 degree flat ends and are fitted tightly in place with a butt joint.

The poplar interior walls are shorter than the exterior walls to create a rabbet on the bottom edge for the bottom panel, and a slightly larger rabbet at the top edge to accommodate the lid. After being dry fitted, I glued the interior walls to the walnut sides, and also put glue along the ends of the poplar boards to butt joint them together. This will reinforce the miter joint of the thin walnut exterior walls, since they won't be reinforced with splines.

The very first box I made got the bottom panel glued in at the same time as the sides, but I quickly realized this was a mistake. If I leave the bottom panel until last, it will be easier to position the interior lid panel when gluing it to the lid. Making sure that the lid fits on properly is very important to this design. So for the other boxes, I just used scrap pieces of poplar as spacers when gluing in the interior walls. The bottom would be added later.

The lids I cut out of maple, the same thickness as the other boards (approx. 0.180" thick). But these I cut out on the laser, and added a different design to each one. On some of them, I gave a quick coat of spray paint before I took off the masking tape from the laser process. This gave a nice dark color to the burned areas.

I made the lids just very slightly larger than the box perimeter. I figured it would be hard to get everything to fit perfectly, and a slight overhang (less than a millimeter) would be preferable to being undersized.

Oh. BTW, one of the boxes came out rectangular instead of square, because I decided to use the two boards that I had messed up with the box joint jig. I just cut off the bad end and mitered them a little shorter. No big deal. If I hadn't, I would have not only wasted the two messed up boards, but the other two sides as well, because I had the perfect number of cut pieces to make five boxes.

I cut poplar pieces for the lid interior, pretty much the exact same size as the box bottom, and dialed in the best fit I could with the shooting board (at 90 degrees). Then I used the box to help me line up the interior lid panel on the underside of the lid to get the best fit. I glued the poplar panel to the underside of the maple lid and held it down with weights.

This was a mistake. It needed stronger and more even clamping pressure. Some of the panels started to curl as the glue dried. I fixed this by adding more glue to the widening joint at the edges and clamping all around with spring clamps.

I sanded all the exterior sides, with the random orbital sander, to 220 grit. The box bottoms needed more attention, as some of them were a little proud of the box sides and needed to be sanded flush. Then I put the first coat of finish on them; 1/3 BLO, 1/3 Poly (oil based), 1/3 mineral spirits. I let this soak in for about 15 minutes and then wiped off the excess. After letting them dry for 24 hours, I came back and sanded the sides lightly with a 220 sanding sponge.

I like the look of an oil rub finish, but there is a trap you can fall into. I call it the "2 coats or 10" trap. Your first two coats of an oil finish (like BLO or tung oil) will completely soak in and give you a matte oil finish. But if you want something with more gloss, you have to do more coats. Well, the next few coats will start to build up a more satin or gloss finish, but it will be patchy, because the wood absorbs the oil more in some areas. To get enough build up on the entire surface with no patchiness, you end up doing ten or more coats and waiting a day between each. That's a lot of tedious finishing time.

This time, I wanted to avoid that trap, but I still wanted more gloss than one or two oil coats can give. So, for the second coat, I tried a new finish that is popular with guitar and gun stock makers. It's called Tru-Oil. You just coat the surface and rub it in until it is all evenly coated and mostly absorbed, and let it dry for 24 hours. Re-coat as desired. It is an oil finish, that also builds up a varnish film finish as you apply coats. One coat of my BLO mixture and one coat of Tru-Oil gave me a satin finish that was not patchy. It could have probably benefited from another coat of Tru-Oil, but this looked good enough. I didn't put the Tru-Oil on the interior of the box. The BLO treatment would be good enough for that.

While I was waiting for the finish to dry, I decided to make a little card detailing when the item was made and from what materials. Sometimes I forget what kinds of wood I used on which projects, and it is always helpful when selling an item to be able to tell the customer what woods were used. So, I made a little card that will stay with the box, and remind the customer as well. I am going to try to do something like this to all my projects in the future.

I added my logo to the bottom of the box. I have a sheet of them printed out that I stained with tea some time ago. When I need one I use the water tearing technique to separate one from the sheet and glue it to the item with pva glue.

Lastly, I put some self adhesive cork pads on the bottom corners to serve as feet, in case the bottom of the box isn't perfectly flat.

And now, some glamour shots.